Some 3 billion fortune cookies are made each year, almost all in the United States. But the crisp cookies wrapped around enigmatic sayings have spread around the world. They are served in Chinese restaurants in Britain, Mexico, Italy, France and elsewhere. In India, they taste more like butter cookies. A surprisingly high number of winning tickets in Brazil's national lottery in 2004 were traced to lucky numbers from fortune cookies distributed by a Chinese restaurant chain called Chinatown.

But

there is one place where fortune cookies are conspicuously absent: China.

But

there is one place where fortune cookies are conspicuously absent: China.

Now a researcher in Japan believes she can explain the disconnect, which has long perplexed American tourists in China. Fortune cookies, Yasuko Nakamachi says, are almost certainly originally from Japan.

Her prime pieces of evidence are the generations-old small family bakeries making obscure fortune cookie-shaped crackers by hand near a temple outside Kyoto. She has also turned up many references to the cookies in Japanese literature and history, including an 1878 image of a man making them in a bakery - decades before the first reports of American fortune cookies.

The idea that fortune cookies come from Japan is counterintuitive, to say the least. "I am surprised," said Derrick Wong, the vice president of the largest fortune cookie manufacturer in the world, Wonton Food, based in Brooklyn. “People see it and think of it as a Chinese food dessert, not a Japanese food dessert,” he said. But, he conceded, “The weakest part of the Chinese menu is dessert.”

Ms. Nakamachi, a folklore and history graduate student at Kanagawa University outside Tokyo, has spent more than six years trying to establish the Japanese origin of the fortune cookie, much of that at National Diet Library (the Japanese equivalent of the Library of Congress). She has sifted through thousands of old documents and drawings. She has also traveled to temples and shrines across the country, conducting interviews to piece together the history of fortune-telling within Japanese desserts.

Ms. Nakamachi, who has long had an interest in the history of sweets and snacks, saw her first fortune cookie in the 1980s in a New York City Chinese restaurant. At that time she was merely impressed with Chinese ingenuity, finding the cookies an amusing and clever idea.

It was only in the late 1990s, outside Kyoto near one of the most popular Shinto shrines in Japan, that she saw that familiar shape at a family bakery called Sohonke Hogyokudo.

“These were exactly like fortune cookies,” she said. “They were shaped exactly the same and there were fortunes.”

The cookies were made by hand by a young man who held black grills over a flame. The grills contain round molds into which batter is poured, something like a small waffle iron. Little pieces of paper were folded into the cookies while they were still warm. With that sighting, Ms. Nakamachi’s long research mission began.

A visit to the Hogyokudo shop revealed that the Japanese fortune cookies Ms. Nakamachi found there and at a handful of nearby bakers differ in some ways from the ones that Americans receive at the end of a meal with the check and a handful of orange wedges. They are bigger and browner, as their batter contains sesame and miso rather than vanilla and butter. The fortunes are not stuffed inside, but are pinched in the cookie’s fold. (Think of the cookie as a Pac-Man: the paper is tucked into Pac-Man’s mouth rather than inside his body.) Still, the family resemblance is undeniable.

“People don’t realize this is the real thing because American fortune cookies are popular right now,” said Takeshi Matsuhisa as he deftly folded the hot wafers into the familiar curved shape.

His family has owned the bakery for three generations, although the local tradition of making the cookies predates their store. Decades ago, many confectioneries and candies came with little fortunes inside, Mr. Matsuhisa said.

COOKIE DETECTIVE

Yasuko Nakamachi, a graduate student from

Japan,

traced the origins of the fortune cookie back a century or more to shops near

Kyoto.

“Then, the companies realized it wasn’t such a good idea to put pieces of paper in candy, so then they all disappeared,” he added. The fear that people would accidentally eat the fortune is one reason his family now puts the paper outside the cookie.

The bakery has used the same 23 fortunes for decades. (In contrast, Wonton Food has a database of well over 10,000 fortunes.) Hogyokudo’s fortunes are more poetic than prophetic, although some nearby bakeries use newer fortunes that give advice or make predictions. One from Inariya, a shop across from the Shinto shrine, contains the advice, “To ward off lower back pain or joint problems, undertake some at-home measures like yoga.”

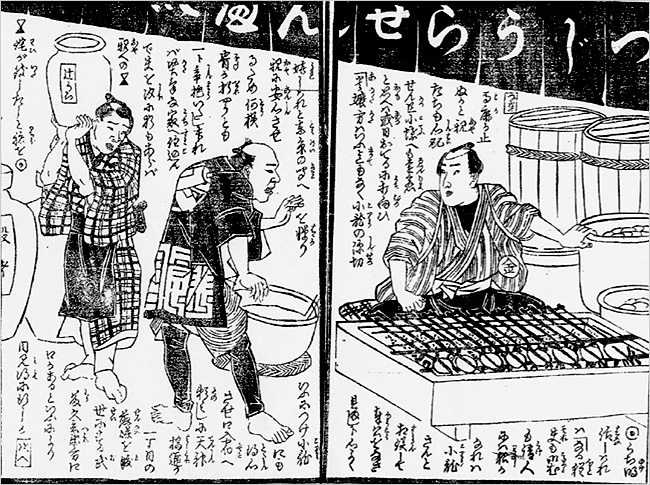

As she researched the cookie’s Japanese origins, among the most persuasive pieces of evidence Ms. Nakamachi found was an illustration from a 19th-century book of stories, “Moshiogusa Kinsei Kidan.”

A character in one of the tales is an apprentice in a senbei store. In Japan, the cookies are called, variously, tsujiura senbei (“fortune crackers”), omikuji senbei (“written fortune crackers”), and suzu senbei (“bell crackers”).

The apprentice appears to be grilling wafers in black irons over coals, the same way they are made in Hogyokudo and other present-day bakeries. A sign above him reads “tsujiura senbei” and next to him are tubs filled with little round shapes — the tsujiura senbei themselves.

The book, story and illustration are all dated 1878. The families of Japanese or Chinese immigrants in California that claim to have invented or popularized fortune cookies all date the cookie’s appearance between 1907 and 1914.

The illustration was the kind of needle in a haystack discovery academics yearn for. “It’s very rare to see artwork of a thing being made,” Ms. Nakamachi said. “You just don’t see that.”

She found other historical traces of the cookies as well. In a work of fiction by Tamenaga Shunsui, who lived between 1790 and 1843, a woman tries to placate two other women with tsujiura senbei that contain fortunes.

|

|

|

Ko Sasaki for The New York Times

CRAFT OF THE CRUNCH

At Sohonke Hogyokudo, handmade fortune cookies are

formed in a wooden mold. |

Ms. Nakamachi’s work, originally published in 2004 as part of a Kanagawa University report, has been picked up by some publications in Japan. A few customers have bought senbei from Hogyokudo, the Matsuhisa family said. But otherwise, the paper has drawn limited attention, perhaps because fortune cookies are not well known in Japan.

If fortune cookies are Japanese in origin, how did they become a mainstay of American Chinese restaurants? To understand this, Ms. Nakamachi has made two trips to the United States, focusing on San Francisco and Los Angeles, where she interviewed the descendants of Japanese and Chinese immigrant families who made fortune cookies.

The cookie’s path is relatively easy to trace back to World War II. At that time they were a regional specialty, served in California Chinese restaurants, where they were known as “fortune tea cakes.” There, according to later interviews with fortune cookie makers, they were encountered by military personnel on the way back from the Pacific Theater. When these veterans returned home, they would ask their local Chinese restaurants why they didn’t serve fortune cookies as the San Francisco restaurants did.

The cookies rapidly spread across the country. By the late 1950s, an estimated 250 million fortune cookies were being produced each year by dozens of small Chinese bakeries and fortune cookie companies. One of the larger outfits was Lotus Fortune in San Francisco, whose founder, Edward Louie, invented an automatic fortune cookie machine. By 1960, fortune cookies had become such a mainstay of American culture that they were used in two presidential campaigns: Adlai Stevenson’s and Stuart Symington’s.

But prior to World War II, the history is murky. A number of immigrant families in California, mostly Japanese, have laid claim to introducing or popularizing the fortune cookie. Among them are the descendants of Makoto Hagiwara, a Japanese immigrant who oversaw the Japanese Tea Garden built in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park in the 1890s. Visitors to the garden were served fortune cookies made by a San Francisco bakery, Benkyodo.

A few Los Angeles-based businesses also made fortune cookies in the same era: Fugetsudo, a family bakery that has operated in Japantown for over a century, except during World War II; Umeya, one of the earliest mass-producers of fortune cookies in Southern California, and the Hong Kong Noodle company, a Chinese-owned business. Fugetsudo and Benkyodo both have discovered their original “kata” black iron grills, almost identical to the ones that are used today in the Kyoto bakery.

“Maybe the packaging of fortune cookie must say ‘Japanese fortune cookie — made in Japan,’ ” said Gary Ono, whose grandfather founded Benkyodo.

Ms. Nakamachi is still unsure how exactly fortune cookies made the jump to Chinese restaurants. But during the 1920s and 1930s, many Japanese immigrants in California owned chop suey restaurants, which served Americanized Chinese cuisine. The Umeya bakery distributed fortune cookies to well over 100 such restaurants in southern and central California.

“At one point the Japanese must have said, fish head and rice and pickles must not go over well with the American population,” said Mr. Ono, who has made a campaign of documenting the history of the fortune cookie through interviews with his relatives and by publicizing the discovery of the kata grills.

Early on, Chinese-owned restaurants discovered the cookies, too. Ms. Nakamachi speculates that Chinese-owned manufacturers began to take over fortune cookie production during World War II, when Japanese bakeries all over the West Coast closed as Japanese-Americans were rounded up and sent to internment camps.

Mr. Wong pointed out: “The Japanese may have invented the fortune cookie. But the Chinese people really explored the potential of the fortune cookie. It’s Chinese-American culture. It only happens here, not in China.”

That sentiment is echoed among some descendants of the Japanese immigrants who played an early role in fortune cookies. “If the family had decided to sell fortune cookies, they would have never done it as successfully as the Chinese have,” said Douglas Dawkins, the great-great-grandson of Makoto Hagiwara. “I think it’s great. I really don’t think the fortune cookie would have taken off if it hadn’t been popularized in such a wide venue.”

Original story posted at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/16/dining/16fort.html