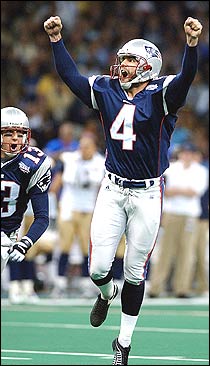

Adam Vinatieri and ball holder Ken Walter reaction to No. 4's Super Bowl-winning field goal in New Orleans last February. (Globe Staff Photo / Jim Davis)

Footloose... and fancy-free

One Super Bowl-winning kick for the New England Patriots altered the trajectory of Adam Vinatieri's life

By Charles P. Pierce, Globe Staff, 08/25/02

Adam Vinatieri and ball holder Ken Walter reaction to No. 4's Super Bowl-winning field goal in New Orleans last February. (Globe Staff Photo / Jim Davis) |

The moment is mute at its heart, which is where you are. There are nearly 80,000 people around you, and you can't hear any of them. There is no music. There is no cheering. There are no grunting linemen, knees cracking, speculating idly about your mother's virtue. The long-snapper, the guy who's looking at you from between his knees, he thinks the other team is stunned that it's come to this. The holder, the guy kneeling at your feet, he's looking at the sidelines, where very large grown men are holding hands like kindergartners practicing the buddy system before a trip to the zoo. A few weeks later, you'll see the films, and there is noise and energy and thousands of cameras flashing all around you, and you won't remember any of it. You look down at the holder, and he nods at you, and you nod back.

Freeze that moment, then, and not the moment when the ball goes through the uprights, and the holder, upright himself now, tackles you and tells you that you've won the Super Bowl, and the confetti comes down like the snow did two weeks earlier, when you kicked two field goals like this one. Freeze that moment and see all the other moments that one moment contains - all the way back to the long plains of South Dakota that run off toward the horizon, all the way back to your ancestor, the regimental-band leader who was lucky enough to stay behind at the fort, waving and saluting and playing his music as a vainglorious general led the Seventh Cavalry off over that horizon and never came back.

Freeze the moment, just for a second, and look down into its silent heart. Then, kick the ball, and watch it spin, end over end and slightly off-axis, and watch everything unreel in its wake, all the way backward through your life before that frozen moment, and all the way forward through what will come next - the parade, a million people shivering in the Boston streets, and that sunny afternoon on a lake where a fisherman will put you on television and ask you to kick a football into the water.

|

Place-kicker Adam Vinatieri signs autographs last month during New England Patriots training camp at Bryant College in Smithfield, R.I. (Globe Staff Photo / Lane Turner) |

Footloose... and fancy-free

(page 2)haven't had a lot of downtime," says Adam Vinatieri, two months after the ball tumbled through the uprights in New Orleans. "It's been fun, and kickers don't get to do this thing very often. I don't think you ever get to prepare yourself for a situation like I had."

He'll be 30 years old in December, and this will be his seventh season in the National Football League, all of them with the New England Patriots. He's darkly handsome, with a quick smile and an earnest, never glib answer to every question. In an office softball league or a pickup basketball game with the guys in accounting, Vinatieri would be the most obviously fit athlete in the group. Only among football players does he seem small.

And his life has changed with the winning kick against the St. Louis Rams in February, although not as much as have the lives of his more celebrated teammates, most notably quarterback Tom Brady, who's raking in the endorsement dollars and the big contract with Cadillac and who's been popping up in the gossip columns with Kennedyish regularity. A year before it all happened, Vinatieri already had settled into a house with his wife not far from Foxborough. He picked up the same $58,000 bonus for winning the Super Bowl that all the Patriots received. He kicked a ball in the studio for Conan O'Brien, and he got an appearance on David Letterman that he recalls as "the coolest thing I ever did, except getting married a year ago January. It's calmed down quite a bit. But I haven't completely moved on."

However, more than any of his teammates, Vinatieri has lived through the improbable arc of his team's success, more even than did the departed Drew Bledsoe, the quarterback who was supposed to be the foundation of that success but, instead, ended his stay in New England as a spare part in the Super Bowl, watching from the sidelines as Vinatieri kicked the 48-yard field goal that removed the idea of "World Champion New England Patriots" - who begin the defense of their title on September 2, in a Monday night home game against Pittsburgh - from the same category of improbability where reside the concepts of President Carrot Top or Academy Award winner Scooby-Doo.

Bledsoe went to Buffalo, and Adam Vinatieri was designated by the World Champion New England Patriots as the team's "franchise" player - an arcane twist in football's labor structure by which Vinatieri lost his right to become an unrestricted free agent in March but which cleared the way for him to sign a three-year, $4.5 million contract, every dime of which is guaranteed. Vinatieri was the first player so designated in the history of the franchise - a remarkable achievement for a place-kicker, a position in which job security often is measured in hours.

"I thought Bledsoe was secure last year, too," Vinatieri says. "I looked around at training camp, and I thought, `That's the most secure guy in football, right there.' For a kicker, you know, you're the least secure guy on the field. You have to prove yourself every game, every kick. You have a bad week, and they might let you slide. You have a couple bad weeks, and you're under the microscope. Have three, and somebody else is at practice, kicking for your job."

There is no more perilous position than one that alternates between times when it is insignificant and times when it is indispensable. "The thing I'll say about kickers is that, if you're doing things right, there are times when you don't need them," explains Patriots coach Bill Belichick. "In hockey, you always need a goalie. No matter how well you're playing, he's going to have to make some saves. With kickers, if you're scoring touchdowns, and the guy's just kicking off, you're doing things right. It's sort of like a relief pitcher. You don't always need them, but when you do, that guy is everything to you."

It wasn't always this way. There was a time, and not that long ago in the history of the National Football League, when place-kicking was simply an extra skill for gifted players to have. (Back in the dim times, of course, when men were men and helmets were leather and noses were flattened, every back was expected to be able to drop-kick placements from all over the field. It was one of the last bits of fossil record tracing football's descent from rugby and soccer.) Don Chandler, who kicked for Vince Lombardi's dynastic Green Bay teams in the 1960s, was a perfectly adequate receiver. (Chandler's backup kicker was Jerry Kramer, an offensive guard.) In the 1970s, when he won a number of games for the Oakland Raiders with last-minute field goals, George Blanda was still the team's backup quarterback.

Since then, however, professional football has steadily specialized. There are linebackers who play only on passing downs. There are two or three different kinds of receivers, who are not even receivers anymore but "wideouts." There are offensive linemen who do not block on running plays and whose sole function it is to protect quarterbacks, almost none of whom can run anymore. There are centers who snap the ball only in situations, like field goal attempts, in which the ball must be snapped a great distance from the line of scrimmage - long-snappers, they are called.

And at the peak of this evolution is the place-kicker, a specialist among specialists. If once the image of the place-kicker was that of a fat tackle called upon to perform a short ballet, it changed in the 1970s when the image transformed into that of Miami's Garo Yepremian, a balding Cypriot with a soccer background, who illuminated the 1972 Super Bowl by attempting to throw a pass out of a bollixed field goal attempt. Not only did the place-kicker not throw like a professional football player, he didn't throw like a recognizable human being. Yepremian's arm came forward, the ball went backward, and he looked like a sea lion tossing a bowling pin. The play was the clearest demonstration of the source of the contempt among workaday players toward the kickers on whom their ultimate success may rest.

"A lot of specialists can't keep up," says Belichick. "I've coached a lot of specialists, and the only other one besides Adam who was really a football player was [punter] Dave Jennings with the [New York] Giants. Adam's not on any special kicker's program. He's on the same program in the weight room. He does the same running everyone else does, the same conditioning. Some kickers have different personalities. He blends in with the team. He's one of the guys."

Except that every mistake that Vinatieri makes, every single one of them, is made out there in the great wide open, with everyone in the stadium looking at him. If quarterback Tom Brady's pass falls short, it could be Brady's fault for throwing the ball badly or the receiver's fault for running an incorrect pass pattern. Blame can be apportioned equally. If an offensive lineman makes a mistake, it's likely nobody will notice until the team meets to go over the game films on the following Tuesday. (There are only two kinds of people who can talk intelligently about offensive-line play: offensive linemen and liars.) Assuming that the long-snapper performs his task correctly and assuming that the holder does the same, Vinatieri's popularity - and, ultimately, his continued employment - follows the ball into the air, every single time.

He had five of those moments last year in which the combined efforts of every one of his teammates rode on what he did, when his job went from insignificant to indispensable. The kick that won the Super Bowl was only the last of them. In October, he beat the San Diego Chargers at Foxboro Stadium. In December, his kicks were the margin of victory in games against the Buffalo Bills and the New York Jets. A little more than a month after beating the Bills, Vinatieri put up his masterpiece. Kicking in heavy snow, in the last game ever played in the old Foxboro Stadium, he drilled a 47-yard kick that sent the Patriots into overtime in a playoff game against the Oakland Raiders. Then, from 23 yards out, he won the game. And then, two weeks later, he went and won the Super Bowl.

"I've never seen anything like what he did last year. Not in my career, anyway," says Ken Walter, the New England punter who holds for Vinatieri's placements. "The different kinds of weather, the importance of the kicks, the fashion in which all those games ended."

The important thing was to make them all the same, so that a kick in the Super Bowl would seem like a kick you made in high school. (When he was lining up the Super Bowl kick, Vinatieri told himself to pretend that it was June and that he was on the practice field in Foxborough.) The key, of course, is to find a way to make all of those moments seem like all the hundreds of kicks that came before, all the way from Louisiana to South Dakota.

"Monotonous," Adam Vinatieri says, "is the way it's supposed to be."

|

Adam Vinatieri in training: "It's been fun," he says of his fame, "and kickers don't get to do this thing very often." (Globe Staff Photo / Chitose Suzuki) |

Footloose... and fancy-free

(page 3)hey left the bandleader and most of the band behind, and that was a lucky thing, indeed. It was June of 1876, and the general was going out to teach Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse a good lesson, and he only needed a bugler for that. So Felix Villiet Vinatieri waited in Fort Lincoln, in the Dakota Territory, waited with the rest of his regimental band for George Armstrong Custer and the Seventh Cavalry to come back from Little Bighorn.

Back in Naples on the south coast of Italy, Felix had been a prodigy on the violin before he was 10. His sister sang opera. In 1859, when Felix was 25, the family immigrated to America, landing in Massachusetts, where Felix's father found work as a piano maker. When the Civil War broke out, Felix signed on with the 16th Massachusetts Infantry as a musician. He stayed in the Army after the war, and he eventually found himself attached to Custer's regiment.

Custer was music silly. It was part of the romance of him. Felix wrote dozens of cavalry marches, and his wife, Anna, became quite friendly with Libbie Custer, the general's wife. When Custer's regiment was on the march, Vinatieri's band marched with it, Felix tootling away on the cornet. Only when the regiment went into battle did the band stay behind. When Crazy Horse fell upon Custer on June 26, 1876, the only musician to die with the Seventh Cavalry was a bugler named John Martini, another Italian immigrant. Later that year, Felix Vinatieri left the Army, settling in Yankton, in western South Dakota, where he and Anna raised eight children. He spent the rest of his life as a working musician, touring for a while with the Ringling Bros. circus and composing a number of ensemble pieces, including "Mosquito Bites of Dakota Waltz" and "Last Indian Campaign March." He died in 1891, 111 years before his great-great-grandson kicked a field goal in the Super Bowl that set off parades on its own.

"We're not sure if he'd had any of his kids before Custer got killed," Adam says. "If he hadn't, and he'd gone with the general, who knows, right? Either way, I'm happy he was able to stay behind on that one."

Adam grew up in Rapid City, South Dakota, a place where distance matters, where family vacations are reckoned in long driving hours over the expansive emptiness of the plains. Paul Vinatieri worked for an insurance company, while Judy Vinatieri stayed at home with the children. (She now works for the Rapid City public schools.) Adam vividly remembers driving five hours to visit relatives in Yankton, across the state. "It was 340 miles," he recalls, "and we made that trip five times a year. I wish they'd had PlayStation or those little TVs back then.

"You're in the middle of the wilderness. You've got the Black Hills, a lot of prairie land. You've got the Badlands. A lot of people, you say `South Dakota' to them, and they think, `Oh, Mount Rushmore.' I'd like to take some guys from the city out there. I think they'd be dumbfounded by the vastness of the place."

He was the second of four children, a serious, active boy who excelled at Pop Warner football - he kicked his first game-winning field goal there - but who had problems with reading and spelling.

"He had trouble with his reading, so he worked really hard at it," says Paul Vinatieri. "The easiest way to get Adam to do anything is to tell him he can't do it."

When he was 9 and in fourth grade, Vinatieri came under the tutelage of Marcy Farrand, a special-education teacher at Woodrow Wilson Elementary School in Rapid City. Vinatieri sees that as the pivotal moment in his life. "You can go one of two ways," he says. "You can let it be a crutch, or you can use it as a steppingstone for good things. At that age, you know, to be a hair behind everyone else, she let me know that if you work hard, good things can happen."

"I think the biggest moment came when he discovered that he could read," recalls Farrand. "It was like, `OK, so I'm not a dumb kid. I can do this. This is not going to be a hindrance for me.' " By the time Vinatieri got to Rapid City High School, he was an A student; in fact, he did so well in science classes taught by Farrand's husband, Mark, that Vinatieri briefly considered a career in medicine. He graduated fourth in his class, and he'd won an appointment to West Point.

Alas, Adam Vinatieri's military career was not as successful as Felix's had been. He missed his girlfriend back home, and he hated the hazing that was so much a part of the plebe year, so he transferred to South Dakota State, where, in 1994, he graduated and ended his college career as the Jackrabbits' all-time leading scorer. The cp9.5NFLcp10.5 scouts considered this so significant an accomplishment that he went undrafted that year. And even though several teams contacted him, he was not even tendered any invitations to come to camp as a free agent.

He borrowed some game films from the school, bought $20 worth of blank videotapes at Wal-Mart, and put together an audition tape that he sent to a number of cp9.5NFLcp10.5 teams. Eventually, Vinatieri came to the attention of Doug Blevins, a kicking guru who was then working as a consultant to the cp9.5NFLcp10.5's World League in Europe. Vinatieri got a tryout for the World League in Atlanta and, in the spring of 1996, he found himself an Amsterdam Admiral.

Vinatieri loved Amsterdam - "It's got a ton of culture," he enthuses - and the place turned out to be a kicker's paradise. The Dutch are, of course, famously insane for soccer, so a 90-yard touchdown pass did very little for them. However, when Vinatieri came out to kick the routine extra point, he was greeted with cheers and singing. Field goals - of which Vinatieri hit nine of 10 in his one season in Amsterdam - occasioned positive delirium. "I'd cheer a running back who scored, and I'd come out to kick the point, and they'd cheer me," he says. "I thought that was cool."

(It should be noted that Super Bowl cp9.5XXXVI cp10.5 was very much an alumni reunion for the Amsterdam Admirals. Not only did Vinatieri play a critical role, but the Rams were quarterbacked by Kurt Warner, who had played in Amsterdam in 1998, after Vinatieri had left.)

In March of 1996, Mike Sweatman, an assistant coach on Bill Parcells's staff in New England, saw Vinatieri at the World League training camp. However, Vinatieri already had signed with Amsterdam. Sweatman got him a tryout with the Patriots after the Admirals' season ended. It was a delicate situation. Parcells was quite attached to Matt Bahr, a veteran kicker whom he'd coached with the New York Giants. In the previous three seasons with New England, Bahr had kicked 50 of 67 field goals, but his skills were obviously fading, and Parcells wanted a player who could kick off as well as kick field goals.

"Coach Parcells said it many times - that if he could have Matt Bahr as his kicker for his whole career, he'd be happy," Vinatieri says. "Matt was sort of in the twilight of his career, and I was this young guy who had potential, and coach Parcells said the team was going in a new direction. And besides, he figured, if this kid does a crappy job, Matt can be here in a week."

Vinatieri won the competition on the strength of his kickoffs. His career did not start well. In his second game with the Patriots, against the Bills in Buffalo, he missed all three of his field goal attempts, including bouncing kicks off either upright. A week later, he missed two more against Arizona. A week after that, against Jacksonville, he bungled both an extra point and a field goal before finally winning the game with a 44-yard field goal in overtime. It was his fifth field goal of the day, but the misses seemed to matter more. At the postgame press conference, Parcells expressed surprise that Vinatieri had kicked five field goals successfully.

"Coach Parcells doesn't sugarcoat anything," Vinatieri explains.

However, Parcells stayed with him, and Vinatieri missed only three more attempts the rest of the 1996 season. He got big points with Parcells that season when he chased down and tackled Dallas running back Herschel Walker on a kickoff return.

Over the next five years, Vinatieri became a solid, consistent kicker, even as the Patriots' fortunes waxed and waned and waxed again with astonishing speed. The team has been in the Super Bowl twice in five years. In between, it slid into mediocrity. Vinatieri was one of the few constants; in 1998, during a 9-7 season at the beginning of the collapse, he kicked 31 field goals, his career best. When Belichick came aboard, and the team began to right itself again, Vinatieri was prepared for it.

"In Adam's case," says Bill Belichick, "he really integrates himself into the team. I've coached a lot of specialists, and he's only one of a couple of specialists who were almost actual football players." He doesn't stay behind, this Vinatieri, when everybody else marches away.

|

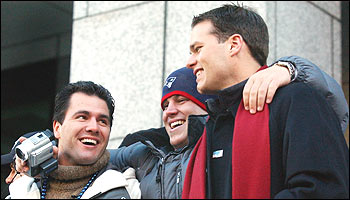

Super Bowl celebrants (from left) Adam Vinatieri, long-snapper Lonie Paxton, and quarterback Tom Brady during Boston's parade. (Globe Staff Photo / Jim Davis) |

Footloose... and fancy-free

(page 4)verybody gets famous. That's what happens when you win the Super Bowl. The kicker gets famous, naturally. The babbling owner gets famous. The coach gets famous. The handsome young quarterback gets Elvis-famous, of course. And even the guy who saw the whole thing first through his knees, and upside down, gets famous.

Lonie Paxton is 24, blond and burly. A Californian born and raised, he could be the bouncer at a beachfront club, the kind of bouncer that can send you to the sidewalk with a look. Last year, Paxton got famous because, after he snapped the ball on what would become Vinatieri's game winner against Oakland, he ran downfield, flopped to his back in the end zone, and began wildly making angels in the snow. He did the same thing in the Super Bowl. Alas, AstroTurf is a less conducive medium for snow angels than is, for example, snow, so Paxton's art suffered.

"I guess that's my trademark move," he says. That's how famous you get when you win the Super Bowl. The long-snapper gets a trademark move - and he had to hire an accountant, too.

"We need consistency. We still need consistency," Paxton says. "We can't win the Super Bowl and then come out here and miss 10 kicks in a row. It's an edgy position. So is being the holder, so is being the long-snapper. It's got to be 10 out of 10."

They are an unlikely trio. There's Paxton, and there's Vinatieri, who's as dark as Paxton is blond, and there is Ken Walter, the holder, balding and who, even at only 30 himself, looks like the guy who's trying to teach the other two calculus while they throw spitballs at the back of his head.

They are the apex of specialization, the three of them, and the fulcrum on which was lifted all the fame, fortune, and Cadillac Escalades of the past, giddy half-year.

All of them live precarious lives, even now: Walter came aboard last year to punt as well as to hold for Vinatieri, because Lee Johnson, the incumbent, was summarily dismissed after one bad game. The team's success - and the trio's continued employment - depends on the synchronous operation of a dozen small movements. One bad snap. One bungled hold. One missed field goal. Seasons can turn on any one of those things.

"It takes some time to get used to each other," Walter admits. "Like, I'd been holding for lefties for the last four years. Now, with Adam, I had to switch all my hand-eye stuff around. I'm catching with the opposite hand, spinning with the opposite hand. With Lonie, who's a great snapper, it all kind of clicked the first week."

They are a unit within the unit, kidding one another in Vinatieri's truck before practice, practicing in all kinds of weather. In fact, when conditions drive the rest of the team indoors for practice, the three of them stay outside, because sooner or later they will have to execute what they do in a downpour or a blizzard or with the wind swirling around them. Vinatieri walks the field before every game, stomping the turf, looking for soft spots and hard patches. Leaving aside that in the Super Bowl, the field goal that made them most famous was an easy one - 48 yards in a dome, off a flat, artificial surface, in a captive, windless atmosphere. "One day," Vinatieri says, "somebody should build me a dome. I'm a big fan of domes."

Instead, there is a new stadium - the biggest, most luxurious piece of evidence in support of what Adam Vinatieri's kick wrought last February. The old joint, the one that closed in the snowstorm against Oakland, the one that always looked like a project that Albert Speer had abandoned in 1933, is nothing more than a pile of concrete and twisted iron atop a huge mound of dirt. The new one gleams and shines on a bright spring morning, a little ways down the hill.

This is the way eras change. The old place was strange and full of comic history. The Patriots were a burlesque for so much of their history; the old stadium didn't open until the plumbing was tested, and the plumbing was tested by having every member of the front office dispatched to the various facilities for an ensemble flush. There were crowds that so closely resembled a gathering of Visigoths that the Monday Night Football package simply refused to return. There were teams that were so bad that even the maniacs stayed home. It would have been completely in keeping with the karma of the place had the last activity there been a gladiatorial brawl.

Instead, it all ended joyfully, a ball spinning through the gentling blizzard and a big ol' football player on his back, making angels in the snow. "The thing about it is that certain people are put in the spotlight," says Adam Vinatieri. "People might remember a picture, but it truly was a team effort." A month later, another kick later, and his long-snapper needs an accountant, and Vinatieri's on Letterman, and there's a gaudy new stadium that sparkles but is as empty of memories as the dome was windless.

Vinatieri's already walked the turf of the new place. He's felt the ways that the wind will come at him - gentle now, but razorish and wild come November. He stepped it off, two steps over and two steps back. There is a moment out there, waiting. There's a band ready to play.

Charles P. Pierce is a member of the Globe Magazine staff. (8/25/02)