By LEE JENKINS New York Times 2/22/07

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz., Feb. 21 — Most major league pitchers throw a fastball, a

curveball, a slider and a changeup. Some mix in a sinker. The experimental

ones use a knuckleball. None of them throws a gyroball, at least not on

purpose.

For most of the past decade, the gyroball seemed to exist mainly in

Japanese video games and cartoons. It was a funhouse pitch with a comic book

name.

When Japanese television analysts tried to deconstruct the mystifying

slider thrown by

Daisuke Matsuzaka, they called it a gyroball, partly because the pitch

seemed to come from another world.

Matsuzaka says he does not throw any such pitch in games — but when he

signed with the

Boston Red Sox this off-season for $52 million, American baseball fans

were forced to confront the mystery.

Is

the gyroball a myth, or is it real? And if it is real, what exactly is it?

Is

the gyroball a myth, or is it real? And if it is real, what exactly is it?

Kazushi Tezuka 手塚一志 says he has the answer, and he flew from Japan to the United

States this week to reveal it. Tezuka, a Japanese trainer who is credited with

creating the gyroball 12 years ago, walked to the mound at Scottsdale Stadium

on Wednesday to show off his invention.

Tezuka used a standard fastball grip. He went into a basic motion. Only at

the end of his delivery did he deviate. He turned the inside of his throwing

arm away from his body and released the ball as if it were a football, making

it spiral toward home plate.

The pitch started on the same course as a changeup, but it barely dipped.

It looked like a slider, but it did not break. The gyroball, despite its zany

name, is supposed to stay perfectly straight.

“That’s it!” Tezuka said, laughing hysterically on the mound. “That’s the

gyro!”

For all of the kids who launch balls around the backyard, baseball is slow

to invent new pitches, and even slower to recognize them. The last pitch to be

adopted by major leaguers was the split-fingered fastball, about 30 years ago.

The gyroball is not going to revolutionize the sport. Like a four-seam

fastball, a four-seam gyroball is designed to surprise hitters with its speed.

Like a changeup, a two-seam gyroball is designed to fool hitters with its

slower pace.

“I think it’s basically a myth, but it’s like a lot of myths in baseball —

it can be useful,” said Robert Adair, who wrote “The Physics of Baseball.” “If

you’re a batter and you think a guy occasionally throws this pitch, it is

something extra to worry about.”

In many ways, this has been the winter of the Japanese pitcher. Matsuzaka

joined the Red Sox. Kei Igawa signed with the

Yankees. The gyroball dominated the blogosphere. Following the mania,

Tezuka was overjoyed. But he was also frustrated.

No

one understood his pitch. It was compared to a screwball even though it is

released off a different side of the hand. It was compared to a cutter even

though it does not cut. Many American coaches claimed it was the stuff of

fantasy.

No

one understood his pitch. It was compared to a screwball even though it is

released off a different side of the hand. It was compared to a cutter even

though it does not cut. Many American coaches claimed it was the stuff of

fantasy.

So Tezuka came to spring training in Arizona this week with two baseballs

and a DVD. Standing in the

San Francisco Giants’ clubhouse on Wednesday, Tezuka watched a portion of

the DVD with one of the most unlikely viewers — outfielder

Barry Bonds.

The DVD shows Japanese pitchers throwing gyroballs and hitters from around

the world flailing at them. Usually, the hitters are either out in front of

the gyroball or slightly underneath it, expecting the pitch to sink like a

changeup.

One of the hitters on the video, undercutting the gyroball and hitting a

meager pop fly to center field, is Bonds. In 2000, during a major league tour

of Japan, Bonds swung violently at a gyroball from the sidearm pitcher Tetsuro

Kawajiri.

Studying the video in the Giants’ clubhouse Wednesday, Bonds took a moment

to try to identify the pitch. “It looks like a little slider,” he said. Asked

if it could be a gyroball, Bonds shrugged his shoulders. “I don’t know what

that is,” he said.

Tezuka came up with the gyroball in 1995, when he was given a toy known as

the X-Zylo Ultra. The toy, a flying gyroscope, could travel as far as 600 feet

when thrown with a spiral. Tezuka wondered why the motion could not work on a

baseball.

Tezuka sought out a Japanese computer scientist, Ryutaro Himeno, to test

his theory. They published a book in 2001 called “Makyuu no Shoutai.”

Translated, the title of the book means, “Secrets of the Demon Miracle Pitch.”

The gyroball has been exaggerated as often as it has been dismissed. In the

latest edition of “The Physics of Baseball,” published in 2002, Adair does not

refer specifically to the gyroball, but he does write about pitchers who try

to throw the ball with a spiral.

Usually, those pitchers are cricket bowlers.

“It’s a standard cricket pitch,” Adair said. “It’s not as useful in

baseball.”

Still, when Tezuka envisions games in 2017, he predicts that the gyroball

will be part of any pitcher’s repertoire. He estimates that 20 professional

Japanese pitchers already throw it, and 100 youths in his clinics use it. He

believes that the

Mets’

Pedro Martínez accidentally throws a pitch resembling the gyroball.

Tezuka feels so strongly about the gyroball that he has tried to get it

copyrighted. “I couldn’t get that,” he said through Masa Niwa, an interpreter.

For years, American players have warmed up their arms by throwing footballs

during batting practice. Because the gyroball is thrown like a football, it

theoretically reduces stress on the elbow and the shoulder.

Akinori Otsuka, a relief pitcher for the

Texas Rangers, works out with Tezuka in the off-season. Even though Otsuka

does not throw the gyroball, he allows his 9-year-old son to throw it. Tezuka

raves about the boy’s ability.

Tezuka visited the Rangers’ spring training complex Tuesday, mainly to see

Otsuka, but he was approached by several other pitchers. They had the same

questions everybody else does. First, they wanted to know if the gyroball is

for real.

Then, they wanted to know how to throw it.

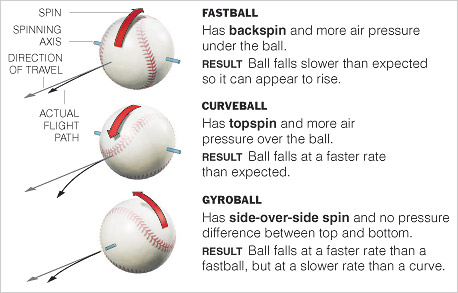

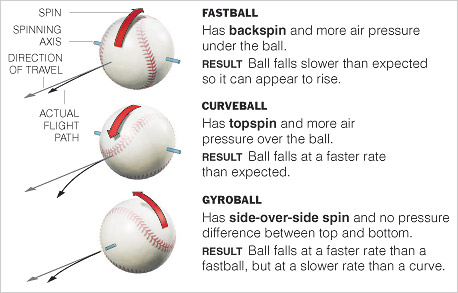

Jeff Topping for

the New York Times: A computer showing how the

mysterious gyroball,

allegedly thrown by Red Sox pitcher Daisuke Matsuzaka, affects

air as it moves forward.

Jeff Topping for

the New York Times: A computer showing how the

mysterious gyroball,

allegedly thrown by Red Sox pitcher Daisuke Matsuzaka, affects

air as it moves forward.

Jeff Topping for

the New York Times: A computer showing how the

mysterious gyroball,

allegedly thrown by Red Sox pitcher Daisuke Matsuzaka, affects

air as it moves forward.

Jeff Topping for

the New York Times: A computer showing how the

mysterious gyroball,

allegedly thrown by Red Sox pitcher Daisuke Matsuzaka, affects

air as it moves forward.

Is

the gyroball a myth, or is it real? And if it is real, what exactly is it?

Is

the gyroball a myth, or is it real? And if it is real, what exactly is it? No

one understood his pitch. It was compared to a screwball even though it is

released off a different side of the hand. It was compared to a cutter even

though it does not cut. Many American coaches claimed it was the stuff of

fantasy.

No

one understood his pitch. It was compared to a screwball even though it is

released off a different side of the hand. It was compared to a cutter even

though it does not cut. Many American coaches claimed it was the stuff of

fantasy.